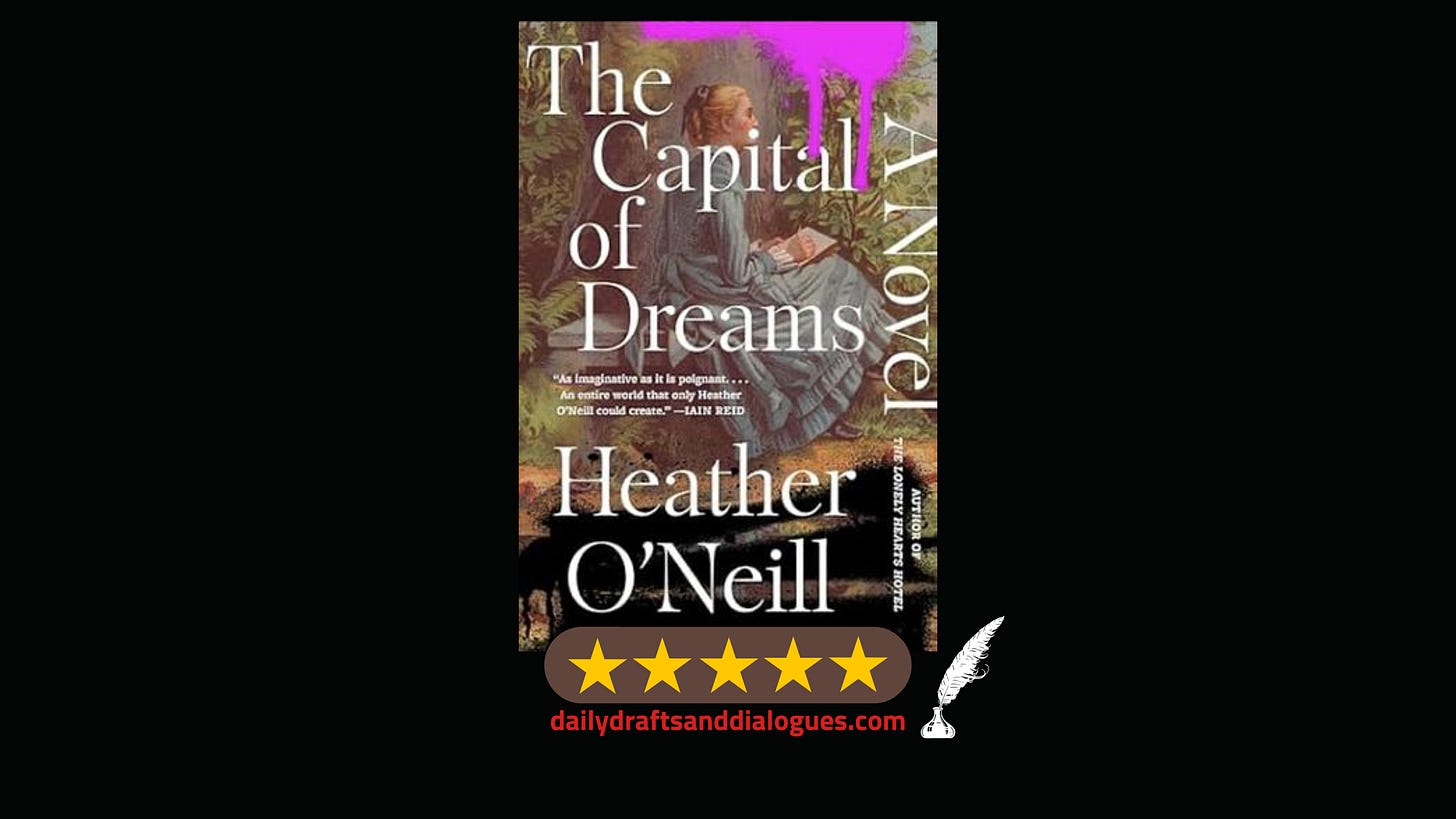

Book Review: The Capital of Dreams

Here’s my review of The Capital of Dreams by Heather O’Neill. Don’t forget to leave a comment if you’ve read it or plan to read it, or if you have any other book recommendations to share.

The Capital of Dreams by Heather O’Neill is a surprising book that may seem simple on its surface, though it is anything but, as it is an interesting and striking example of metafiction unpacked via ruminations and stories told during wartime, which are all intermingled with a complex mother-daughter relationship that unfolds as the main character is co…